What does “identity” stand for? Is it merely a social tag or some loosely constructed cultural label? What does it mean to be a Naga? Is it yet another socio-political identity, or something more? This and many more questions have been discussed in the article by Khriezeno Sakhrie.

What does “identity” stand for? Is it merely a social tag or some loosely constructed cultural label? What does it mean to be a Naga? Is it yet another socio-political identity, or something more? This and many more questions have been discussed in the article by Khriezeno Sakhrie.

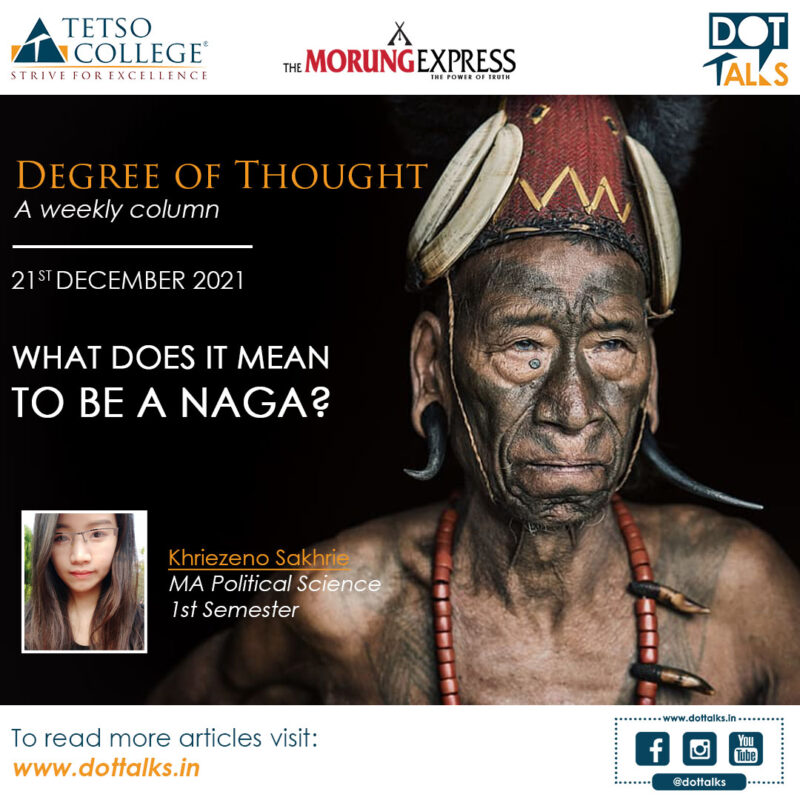

What does it mean to be a Naga?

Being a Naga deals with identity of the Naga. The Naga people are considered to be ‘different’ in the eyes of others, the outsiders. The term Naga came to signify the separate identity of the people. As the Nagas became more united, they began to use the name ‘Naga’ for themselves. The use of the term ‘Naga’, the presence of people of different races and cultures made the Nagas to think in terms of ‘us’ and ‘them’, i.e. ‘us’ meaning the Naga tribes, signifying their oneness and unity, and ‘them’ meaning the outsiders, who are racially and culturally different from them. The Nagas had something in common that made them recognizable as a people, though composed of different tribes and subtribes within.

It is ‘a complex fate’ being a Naga. In our context, it is a double-edged sword because the complexity lies not only in the way ‘outsiders’ view us but also in the way we see ourselves. Being a Naga has never been easy for us. The mystique and negative power of the ‘savage’ has always fascinated the western mind and when we were ‘discovered’ by anthropologists and ethnographers in the 19th century, we became exotic and exciting specimens for them to study, but from their perspective only. Our material culture seems to have caught their imagination in such a manner that the best specimens were spirited away to their museums without any qualms because they were the ‘finders’ and therefore the ‘keepers’. But fortunately for us, though we were stripped of our external Naga-ness, the essential core of our being Nagas could not be obliterated and this consciousness has remained firmly rooted to the soil of our origin.

When we look deep into our hearts and try to compare ourselves with our fellow Nagas, we come to the realization that we do share an intrinsic one-ness in our way of thinking and living. That is why, in spite of the many surface differences we have continued to exist as a coherent group of people. Throughout all these upheavals in our history, what has remained a constant is the amorphous nature of our identity, of being a Naga.

The political aspirations had initially set out to establish the intrinsic worth of our being, our Naga-ness. But the result we see today is a pathetic blend of greed, self-centeredness and mutual suspicion.

Now to the question of how we see ourselves. Among the many divisive elements that add another dimension to these questions, is the tribal divide that has had the most devastating effect on the political scenario both overground and underground. Even if there are professed political parties within the electoral system that is current in the state, when it comes to crunch time, people’s mandates are swayed either by tribal or clan affiliations; party ideology seems to have no influence at the crucial time. The same trend is reflected in the convolutions of the other movement also.

Being a Naga is the realization of the power of unity of all tribes and not for a particular community and by being better warriors by fighting all the negativity and standing for truth for good and for our people as Nagas.

To be proud of being a Naga is to live in peace and harmony with all the tribal communities, to support one another as a community, to care for the state’s economy, to be humble amongst the tribes and within.

The superficial affluence brought in by the imported system seems to have left the village folk far behind and there is an ever widening gap between the haves and the have-nots. This is the real paradox of our existence as a people: the divide between the village and urban ethos. Though all the new money, political influence and modern life-style seem to reside in the urban areas, the real essence of our Naga-ness still remains in the heart of the land: the villages. To ‘belong’ in a village is the first requisite of an individual in building up the notion of identity as a Naga.

It is therefore clear that whatever identity we are trying to forge for ourselves cannot be attained through academic and empirical research alone which can at best lend some authenticity to sites of origin and trails of migration. But it will only be a historical account of the evolution of the Nagas through the ages. Today, identity formation for Nagas has to be in consonance with our present circumstances and informed by a spirit of inclusion of all superficial differences; the diachronic discourse must include the synchronic paradigms that draw the Nagas together at a stage in the history of mankind when the whole of humanity is being inexorably propelled towards the vortex called globalization where identities are made, un-made and re-made. What we ought to do now is to exercise some ‘intellectual flexibility’ and hold on to the essential values that made us what we are as a people, holding us together through countless generations. It is the unity of all tribes to live in peace and harmony as Naga.

The envisaged identity has therefore to be based on the principle of ‘oneness’ that is inclusive of both commonality as well as differences and has to be introspective and inter-relational because the identity perforce will always be multi-layered. Only when we acknowledge these inalienable facts of geography, history and culture that have imposed this pseudo-homogeneity on us and accept the multifaceted identity that we share as a people, the ‘complex fate’ being a Naga will perhaps no longer be so ‘complex!’

Degree of Thought is a weekly community column initiated by Tetso College in partnership with The Morung Express. Degree of Thought will delve into the social, cultural, political and educational issues around us. The views expressed here do not reflect the opinion of the institution. Tetso College is a NAAC Accredited UGC recognised Commerce and Arts College. The editors are Dr Hewasa Lorin, Dr. Aniruddha Babar, Aienla A, Rinsit B Sareo, Meren Lemtur and Kvulo Lorin.

For feedback or comments please email: dot@tetsocollege.org